Environmental Review Laws can Hurt the Environment

Protecting the environment or the status quo?

There’s an alphabet soup of environmental review laws: NEPA, CEQA, CEQR, SEQRA (the list goes on…) that have become a political flashpoint over the past year with “permitting reform” becoming a major national issue.

So what are these laws? Why do they exist? And most importantly, are they actually helping the environment?

A Brief History of Environmental Review Laws

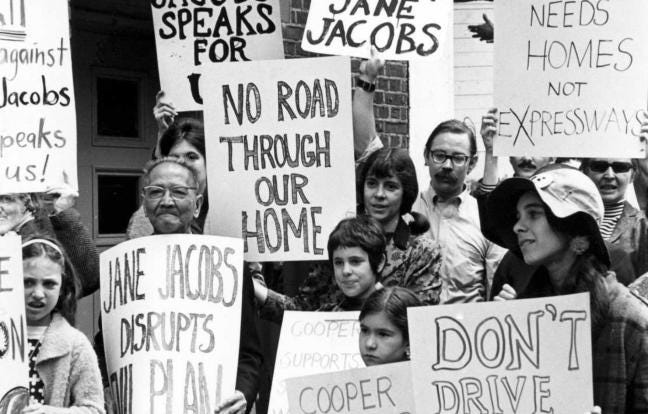

In the 1960’s, we were building a lot of bad stuff. Neighborhoods (overwhelmingly working class minority ones) were frequently being torn down to build urban highways, often leading to protests. A massive oil spill off of Santa Barbara was major news in 1969. The Cuyahoga River in Cleveland was so polluted that it caught fire. The two decades of rapid industrial development in post-WWII America clearly came at a major environmental cost. And there was growing political pressure to slow things down and take a hard look at these environmental costs relative to the benefits of any major new project receiving government funding.

The answer was NEPA - the National Environmental Policy Act, passed with large bipartisan majorities and signed by President Nixon in 1970. NEPA was actually a relatively vague bill, only six pages long - it simply directed federal agencies to “attain the widest range of beneficial uses of the environment without degradation” and required that all federal agencies prepare various levels of environmental review statements to ensure they “appropriately consider” the environmental impacts of their projects. Interestingly enough, NEPA itself never forbade projects from being built that had detrimental environmental effects - it only required those effects to be documented and “considered”.

In the context of highway widening and fossil fuel development, this was a valuable policy that helped environmentalists stop destructive, short-sighted projects with major negative environmental impacts. It’s worth noting, though, that these laws still didn’t stop most environmentally destructive projects, but they at least gave opponents an avenue of potential recourse to slow down some bad projects. Many states adopted similar laws, with Gov. Ronald Reagan signing the California Environmental Quality Act later in the year, which had even more strict requirements than NEPA.

So, what went wrong?

A few things have happened over the past 53 years that have turned these environmental laws from a tool for environmental justice to a major hindrance to the green transition.

1: The types of projects being built changed

This one is simple: stopping a highway going through an urban neighborhood? Great!

Stopping a new wind farm or subway line? Extremely bad!

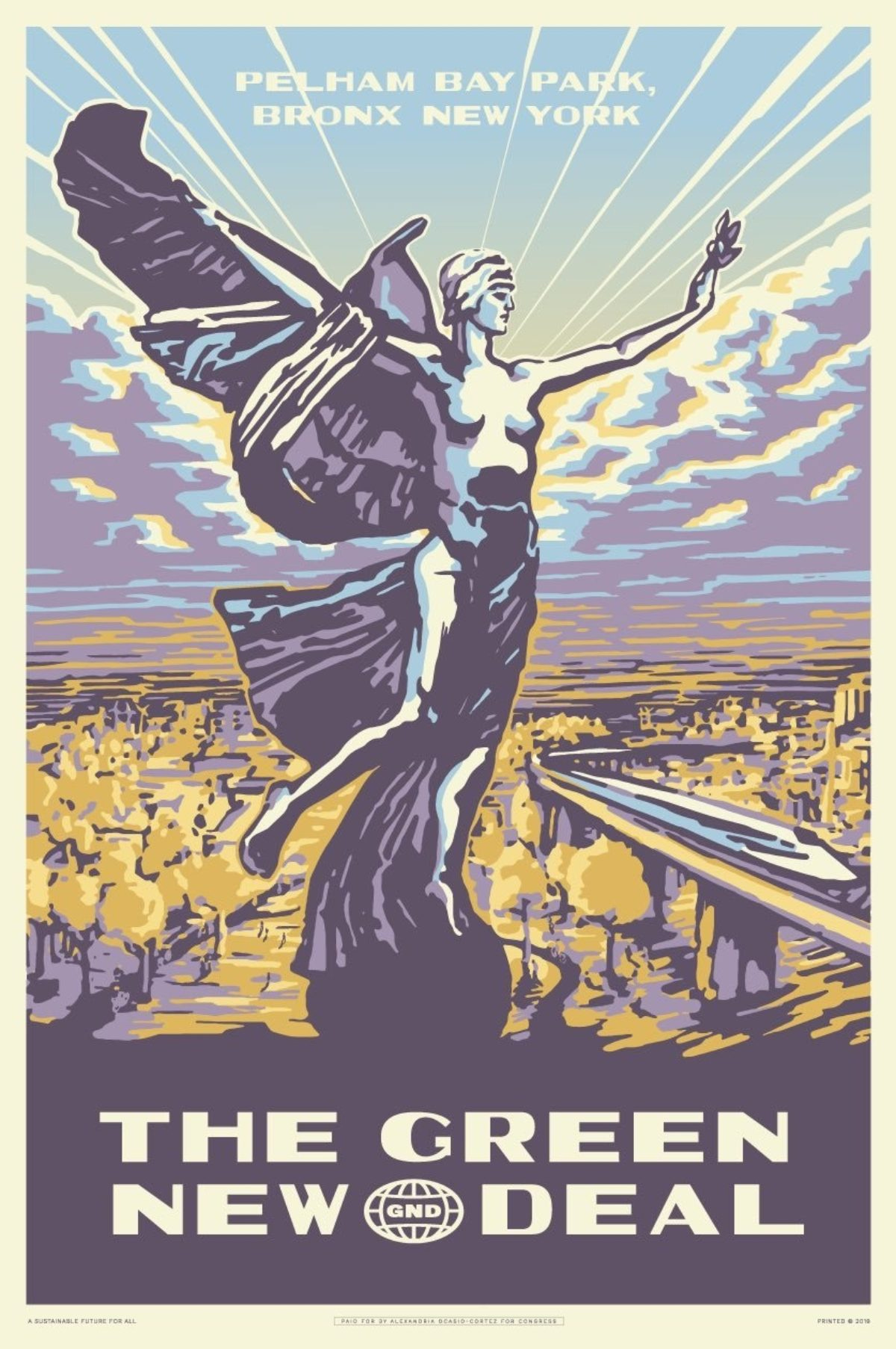

As the world has changed over the past 50 years, we are building a lot more of the good infrastructure projects now. With the recent Inflation Reduction Act funneling billions of subsidies into green energy, there’s massive pressure to build a lot of really awesome green infrastructure from solar plants to offshore wind farms. We know that we need to build this renewable energy infrastructure - that’s why the IRA was passed! So why are we letting NEPA slow us down when we know we need to go forward? Why do we need an environmental review to get rid of an asthma-causing highway that was never environmentally reviewed in the first place?

2: Status quo bias

A major flaw of these environmental review laws is that they fail to consider the environmental impacts of the status quo. A great example of this is congestion pricing in lower Manhattan. We know that congestion pricing works where it has been tried globally in London, Stockholm, and Singapore: It raises money for transit (money that the MTA very much needs!), reduces pollution, and encourages people to take more sustainable forms of transit. Even though the public is often skeptical of congestion pricing at first, once implemented it ends up being extremely popular.

Even though congestion pricing was included in the 2019 New York State Budget, it’s been four years and construction hasn’t even begun, as the MTA spent years simply requesting a simpler form of environmental review (NEPA has tiers of review, the highest of which is an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), the MTA wanted a less-exhaustive Environmental Assessment (EA)). In March 2021, Buttigeig granted the MTA permission to do an EA which, despite being shorter than an EIS, still took 18 months and wasn’t released until August 2022.

In the years that this plan has been undergoing environmental review, the status quo of a lack of congestion pricing has resulted in continued gridlock, pollution, and lack of MTA funding. By delaying projects, NEPA has essentially privileged the status quo in a way that makes it more difficult, lengthy, and expensive to enact projects that will unambiguously change the environment for the better.

More broadly, NEPA came after two decades of environmentally destructive projects, but is now hamstringing us from building new, environmentally friendly projects that can help right the same wrongs that led to NEPA being passed in the first place!

3: The amount of paperwork required has increased

Remember how I said the MTA was granted the right to do a less-intensive “Environmental Assessment” (EA) instead of a full-blown “Environmental Impact Statement” (EIS), guess how long that EA was? It’s 868 pages (and that’s not considering 3,000 pages of appendices). You can read it here if you want. And, surprise surprise, It found that congestion charging would be a great way to reduce pollution and congestion while raising money for the MTA.

This reflects a broader trend of environmental reviews becoming more lengthy, and therefore longer to write/more costly. This can be seen if you go to the MTA’s congestion pricing assessment and look at all of the engineering consultants who helped compose the documents - they aren’t cheap!

4: Lawsuits have been weaponized in bad faith by wealthy, anti-environmental actors

Another major problem with NEPA and similar environmental laws is that its vagueness means that the primary mode of enforcement is via lawsuit. Because NEPA lacks clearly prescribed rules about what should be prohibited, many projects end up in years of litigation. And the only thing more expensive than engineering consultants are the lawyers who are putting in thousands of hours to defend projects that are being litigated.

Perhaps more troubling is that this process essentially means that rich NIMBYs have the best means to fight against a project. For example, billionaire heirs and McKinsey partners are funding a recent lawsuit against an offshore wind farm in Long Island. Billionaire homeowners in The Hamptons trying to stop green energy are closer Disney villains than environmentalists.

Another example is a recent CEQA case where a wealthy Berkeley homeowner, Phil Bokovoy, sued UC Berkeley, saying that an increase in enrollment is a form of pollution. And the crazy thing is that the courts agreed with him! A superior court judge forced Berkeley to rescind 5,000 acceptances because the students could “result in an adverse change or alteration of the physical environment”. This was so absurd that state legislators thankfully passed a new law exempting student enrollment from being viewed as pollution and preventing Berkeley from rescinding thousands of acceptances. While this case was so flagrant that it motivated legislators to act, there are tons of other ridiculous CEQA rulings stopping housing and transit construction that should be motivating similar outrage.

5: Even when projects are built, the uncertainty around the NEPA process drives up costs and delays construction

I grew up in Montgomery County, Maryland. Ever since I was a little kid, the idea of a “Purple Line” connecting the two ends of the Metro Red Line in Bethesda and Silver Spring, along with the Green Line in College Park was highly supported in the community, except for a small group of rich anti-transit homeowners in Chevy Chase (if that town sounds familiar, it’s because Bretty Kavanaugh lives there).

Over the past decade, that group of affluent homeowners has funded frivolous lawsuit after frivolous lawsuit, eventually finding a sympathetic judge (appointed by George Bush), who halted construction for years. The most absurd lawsuit claimed there was a rare microscopic fish that only existed in a spring near the proposed train tracks. A scientist spent a week looking through the entire path and found that the microscopic fish in question never existed.

Even though the Purple Line was eventually approved, the problem with this outcome is that these delays in construction have made it far more difficult to hire contractors, secure funding, and actually build the rail line, resulting in over four years of delays and a billion dollars in cost overruns (although Larry Hogan’s mismangement of the project has been a major contributing factor as well). Furthermore, the risk of litigation injects uncertainty into a project, and by increasing risks, construction subcontractors demand higher fees.

How do we fix it?

This has all added up to the point where NEPA and similar state/local laws have preserved an unsustainable status quo. Ironically, a NEPA-style analysis of NEPA itself (and similar state laws) would probably find a lot of negative environmental impacts from the law, ranging from years of delays in building green infrastructure to stopping housing and contributing to increasing homelessness.

It’s clear that we need some sort of permitting reform. While Manchin’s permitting reform proposal wasn’t perfect, it would have helped to accelerate the construction of electricity transmission for green energy, which is a necessity if we want green energy to replace coal and gas. I worry that Manchin’s proposal is the best we would have been able to get while Democrats had a trifecta, and now that Republicans control the House, any potential permitting deal would be even worse of a mixed bag (by speeding up fossil fuel permitting as well).

However, instead of just criticizing Manchin’s proposal, progressives need a tangible path forward for ensuring we can build the infrastructure we need for a green transition:

1. Streamline approvals for green projects

It’s objectively silly for a wind farm to face the same level of environmental scrutiny as a coal plant, or for a new subway line to face the same level of scrutiny as an urban highway. Oil & gas projects already have some categorical exclusions that exempt them from NEPA. We need similar exemptions for clean energy construction and transmission (particularly geothermal, solar, and wind), preventing rich NIMBYs from taking advantage of the law in a way that just continues our reliance on fossil fuels. The same goes for transportation: any bike or transit infrastructure should be presupposed to reduce carbon emissions and should be granted fast-track approval.

Part of this streamlining should include limits on judicial injunctions that are responsible for stopping projects. Looking at the Purple Line in Maryland, the fact that a single judge can arbitrarily stop a multi-billion dollar transit project is absurd, even though the judge was eventually overruled upon appeal.

2. Create stronger guardrails against fossil fuel infrastructure

The other half of the equation should be preventing infrastructure that makes it harder to accomplish a green transition. A good example of this is the “fix it first” provision in the House-passed INVEST Act which would have required state highway departments to ensure that existing roadways are well maintained before being able to use funds on new highway expansions (unfortunately, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill that ended up replacing the INVEST Act did not have this provision). Rather than relying on a convoluted lawsuit process of NEPA, Congress has the power to simply prohibit (or at least discourage) spending that would increase emissions.

3. Staff up agencies

One of the reasons it takes so long to complete environmental reviews is that many government agencies are chronically understaffed due to uncompetitive pay, convoluted hiring processes, and limited career progression opportunities. As a result of understaffing, many government agencies are forced to rely on (extremely expensive) third-party engineering consultancies. Thankfully, this was included in the IRA, but should be expanded for state and local agencies as well.

For what it’s worth, this is a problem that goes far beyond environmental review. Understaffed transit agencies that are overly reliant on third-party engineering firms are part of the reason transit is so expensive to build in this country more broadly.

4. Reform Federal & State laws

Fixing NEPA isn’t enough: we need to fix the state laws like CEQA that are often more onerous than NEPA itself. There’s already movement among elected officials in California and New York (so if you live in those states, it doesn’t hurt to call your state legislators and tell them you support these proposals).

Additionally, the federal government could incentivize streamlining state laws by making that a requirement or scoring criteria for certain federal funds.

5. Focus on the big picture

I get why some progressive groups like NEPA: it’s one of the only tools available to push back against polluting infrastructure. However, it’s important to adopt a big-picture approach here: we shouldn’t let a fear of bad projects let us stop a bunch of good projects. Texas, which doesn’t have many environmental protection laws, has been able to rapidly expand wind energy precisely because they don’t have a bunch of laws that make it harder to build them. As renewable energy becomes cheaper than coal, wind and solar will replace fossil fuels like coal, but only if we let it get built.

Progressive groups need to come to the table to help ensure that a future permitting regime does a better job at stopping the genuinely bad projects without slowing down the necessary green projects. The green transition will be the largest project of our generation, and we can’t do it without freeing ourselves from laws purposefully designed to slow down the approvals of projects.

Additional recommended reading on this subject:

Institute for Progress: How to Stop Environmental Review from Harming the Environment

Vox: Manchin’s permitting reform effort is dead. Biden’s climate agenda could be a casualty.

Ezra Klein: All Biden Has to Do Now Is Change the Way We Live

Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT): To better address the climate crisis, the US must reform its permitting process

It's complicated.

NuScale's NRC submittal was over 12,000 pages and cost of the entire process >$1 billion.

"Lawsuits have been weaponized" on both sides. There is no escaping "sue and settle" by environmental groups in that debate. Examples everywhere.

The existing laws aren't even being applied equally. Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) and wind developers is only one example.

It's complicated. It requires balance. Everyone wants clean air, water, healthy ecosystems, reduced impact/unit of GDP, lower CO2 emissions/capita, etc.

Good stuff! We badly need permitting reform. America is not a museum.

Fossil fuel infrastructure is more complicated than it seems. Look at natural gas demand in New England. There's a shortage of infrastructure to bring gas from Pennsylvania. But New Englanders still need to heat their homes. So now we buy gas shipped from the Caribbean, at the Europe price. This drives up costs for everyone, and screws over poor people the hardest.

When we don't produce fossil fuels in the US, the demand doesn't go away. We just wind up importing it from abroad.

The only way to save the planet from climate change is to create abundant energy sources that don't emit GHGs, and can reliably meet society's energy needs 24 hrs a day, 365 days a year. Nuclear energy is the closest we've got. Now that's an area with serious permitting issues!