Are Electric Vehicles the Future of Transportation?

What does truly sustainable transportation policy look like?

In casual discussions with smart people, decarbonization of transportation is frequently taken for granted. “Oh, we have EV subsidies, we’re all set on decarbonizing transportation” is a take I have frequently heard. Is it really that simple? As with most things in life, the answer is a bit more complicated than that, so I’m going to look at the pros and cons of EVs and how they can fit into a long-term sustainable transportation policy.

For those in a rush, here’s the TL;DR: EVs are the future of cars, but cars are not the future of transportation. Cars will always be one of the primary ways we get around, and EVs are, on the whole, much better than gas-powered cars. But EVs also have some real downsides that must be considered and mitigated. And more broadly, we need sustainable transportation and land-use policy that doesn’t lock people into car dependency and leads to a future with more mobility and less driving.

Benefits of EVs:

1. Reduced Emissions

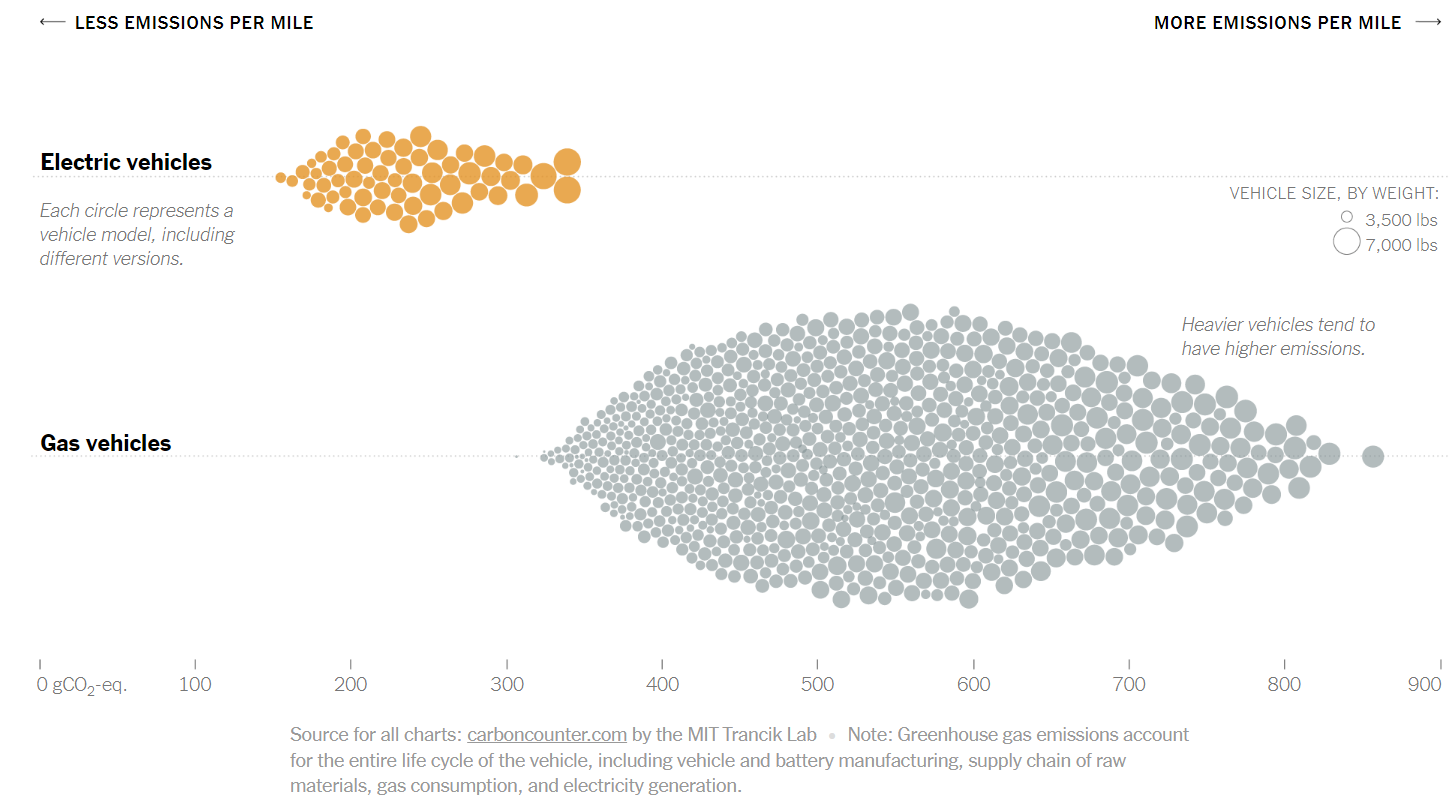

The most obvious benefit of EVs is that they have zero direct tailpipe emissions compared to cars with traditional internal combustion engines (ICE). Since the cars run on electricity, the only emissions are from electricity generation, which means that an EV being charged by a solar/wind/hydro/nuclear/geothermal grid is one that has fewer emissions than a coal/gas grid. However, even when factoring in the emissions from electricity generation, the average EV still has fewer tailpipe emissions than an ICE. Some right-wingers like Tucker Carlson have argued that the emissions of manufacturing electric car batteries and electricity generation create more emissions than gasoline, however, this is patently false. While the manufacturing of an EV battery does have some embodied carbon, on the whole, an electric car is still much better for the environment than a comparable ICE car.

2. Political economy benefits from reduced reliance on oil

If there’s anything we’ve learned from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it’s that reliance on foreign oil is, well, pretty bad. It feels like the West is constantly playing wack-a-mole with a range of unsavory dictatorships from Russia to Saudi Arabia to Venezuela when it comes to deciding which country we import oil from. Being able to rely on domestic energy (particularly renewables) will make it easier to isolate these dictatorships instead of begging OPEC to release more oil to lower gas prices.

This also brings us to the domestic political economy benefits of reducing reliance on gasoline. With signs advertising the price of gasoline prominently displayed across the country, gasoline prices have become a key determinant of consumer confidence. As a result, this gives foreign dictatorships a disturbing amount of power over domestic politics. If Mohammed bin Salman is mad at President Biden for criticizing his murder of Jamal Khashoggi, he can tighten oil supply, driving up gas prices and hurting Biden’s approval rating and election performance. In a future where gas prices are irrelevant and everyone is using an EV, this power largely disappears from petro-dictatorships.

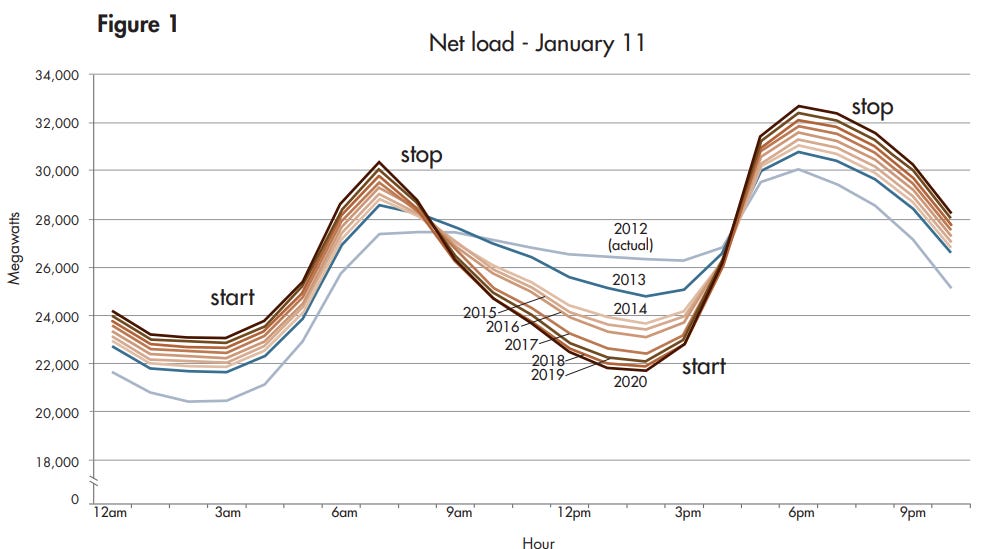

3. EVs can be used as in-home battery storage

One well-known issue with renewable energy, particularly solar and wind, is that it’s intermittent. If the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining, not a lot of energy is being produced, which is why fossil fuels (and nuclear) are typically used as a form of baseload power during cloudy, wind-free days. This is particularly notable in California (where rooftop solar is common) as seen above with external energy demand dipping during the day and then spiking during the evening as the sun sets. Here, EV batteries present an opportunity: they can store energy during sunny and windy days when renewable energy is abundant and then feed energy back into the grid (or your house) on cloudy days (or at night), helping smooth out energy consumption. Impressively, new EV batteries can store enough electricity to power your house for three days!

4. It’s already happening

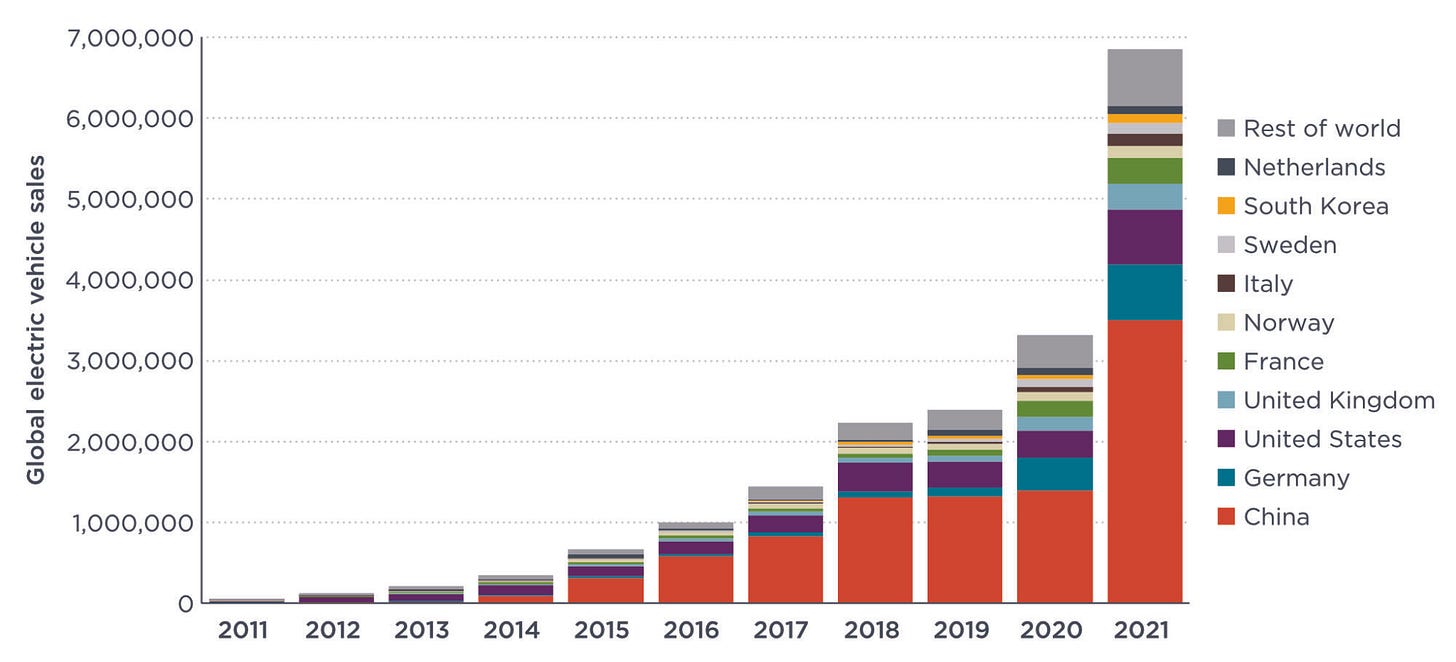

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has tens of billions in tax credits for EVs, with a $7,500 tax credit for new vehicles that meet sourcing requirements. Many states, including California, New York, Massachusetts, Washington, and Maryland have already banned the sale of new gas-powered cars starting in 2035, and the entire EU has done the same. Some countries, such as the UK and Norway have taken even more aggressive stances, planning to ban gas cars in 2030 and 2025, respectively.

Furthermore, as the cost of EVs declines due to scale and government subsidies, sales are increasing exponentially. The shift to EVs is happening, the question at this point is not “if”, but “when” and “how fast”. And perhaps more importantly, what are the downsides of EVs that we should try to mitigate?

The downsides of EVs

1. They’re heavy

In the 1950s, the government ran a series of tests to see how the weight of a vehicle impacts the wear and tear on roadways. The result was that wear and tear increased at the fourth power of vehicle weight. This means a car that is twice as heavy causes approximately 16x as much road wear and tear. Since electric cars are generally 33% heavier than their gasoline-powered equivalents due to the weight of the battery, this means that the average electric car causes more than 3x as much roadway damage as gas equivalents, which means more money will be required to maintain our highways and streets. We already spend over $20B every year on maintaining highways, and a recent study found that we will need to spend $200B every year to bring all of our highways up to a state of good repair. EVs will make that even more difficult.

Another problem with heavier cars is that they are more dangerous. The head of the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) expressed concern of “increased risk of severe injury and death for all road users from heavier curb weights and increasing size, power, and performance of vehicles on our roads, including electric vehicles”. EVs typically accelerate faster than gas cars, and the trend of faster, heavier cars will likely continue increasing pedestrian deaths if regulators do not redesign our cars and roadways to make them safer for pedestrians.

2. Highway maintenance funding will dry up

A significant portion of highway construction and maintenance spending is funded by the gas tax (side note: many assume that the gas tax covers all highway spending, however, the tax has not been raised in decades, and as a result the federal government has transferred over $270B on top of the gas tax for highway spending). Once we shift over to electric cars, that revenue will shrink even further, and when combined with the increased wear and tear from heavier electric cars, we will need to find new ways to fund road repair. One option is a tax on vehicle miles traveled (VMT), and the bipartisan infrastructure bill requires the Department of Transportation to study what this could look like in the future. While this is inherently a political problem, it is one that will require political capital to address.

3. EVs require minerals that can be difficult to obtain

Lithium-ion batteries require a range of minerals, specifically five critical minerals as defined by the US government: lithium, cobalt, manganese, nickel, and graphite. We are largely reliant on imports for these minerals, and many nations that we import from are highly unstable and have unsafe working conditions (for example, more than half of the world’s cobalt comes from The Democratic Republic of the Congo, which relies on modern-day slavery and child labor in the mines for just a few dollars a day. That’s not to say this is an inherently unsolvable problem, as a combination of improved governance in mining countries (along with support from multinationals and richer western nations) plus consumer demand for ethical battery sourcing could solve this. But it’s another example of how just because even though EVs may solve one problem (in this case, petro-dictatorships), others can pop up in its place.

They’re still cars

Cars are incredibly useful, nobody will deny that. But I think there’s a valid fear that EVs just slap a bandaid of emissions reductions on the very-real downsides of cars that will still exist. Many of these downsides are tied to the fact that a three-ton car is simply a very inefficient way for a single person to get around. The amount of infrastructure required is massive (a recent Harvard study calculated the total social cost of cars in Massachusetts alone to be $64B). Some more specific issues with cars that could be exacerbated by EVs include:

Traffic Fatalities

42,915 Americans died in traffic in 2021, comparable to the number of gun deaths in our country. While the US saw traffic deaths decline from 1975-1995 due to safety regulations around seatbelts and airbags, we have fallen far behind other developed nations due to having more, bigger cars and dangerously designed roads. EVs do not fix this problem. If anything, the heavier weight of EVs makes them more dangerous.

Non-tailpipe pollution

While EVs have zero direct tailpipe emissions, they still cause pollution from brake dust, tire dust, and road surface wear and tear. Basically, a 5,000+ pound vehicle going at high speeds kicks up a lot of dust due to friction and that fine dust becomes pollution, and the increased weight of EVs potentially increases that type of pollution.

Negative impact on land use/cities

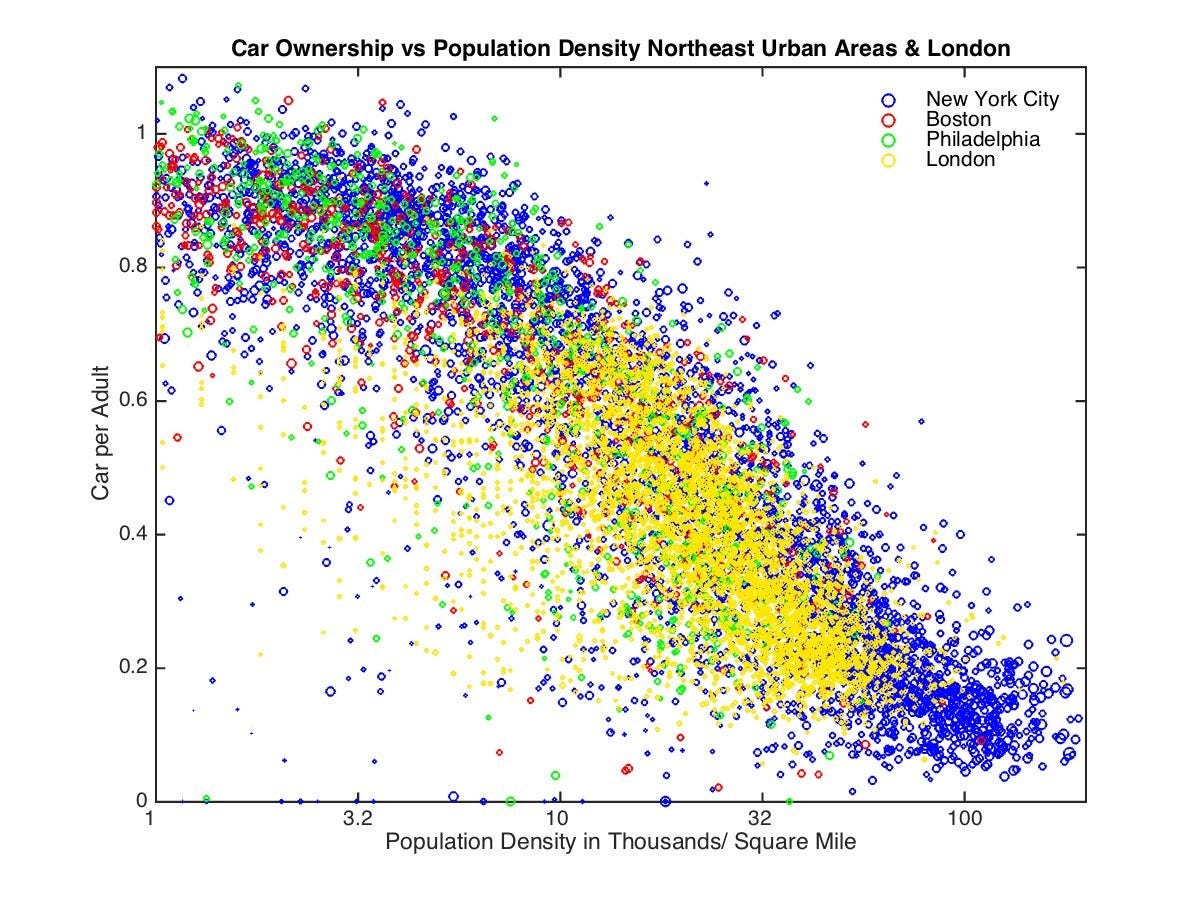

From a geometric standpoint, dense cities are simply incapable of accommodating mass car ownership, and cities built around cars are less pleasant and more sprawling. Shifting to EVs without denser, pedestrian/transit-oriented land use will exacerbate trends of suburban sprawl, leading to more traffic, expensive rents, and unpleasant urban areas. Since suburban homes are typically larger and have no shared walls, they are less efficient for heating and cooling, which is another large source of carbon emissions.

Where do we go from here?

On the whole, EVs are far better than gas cars when it comes to environmental impacts. But, the idea that EVs alone will “fix” transportation is a pipe dream. We need policies that both mitigate the specific downsides of EVs and shift to a more sustainable land-use and transportation paradigm. Here’s what that would look like:

Incentivizing smaller cars that weigh less. The 9,000-pound electric Hummer is still a policy failure that will cause a ton of wear-and-tear on our roads and threaten pedestrians. Simple policy levers to accomplish this include:

Taxes on heavier cars due to those increased costs (DC is already proposing this and California lawmakers have introduced a bill to do the same)

Factoring pedestrian safety into crash test ratings (currently, the US doesn’t evaluate cars at all on how their design impacts pedestrians!)

Scaling federal EV tax credits by vehicle weights, so lighter cars get more tax credits than trucks

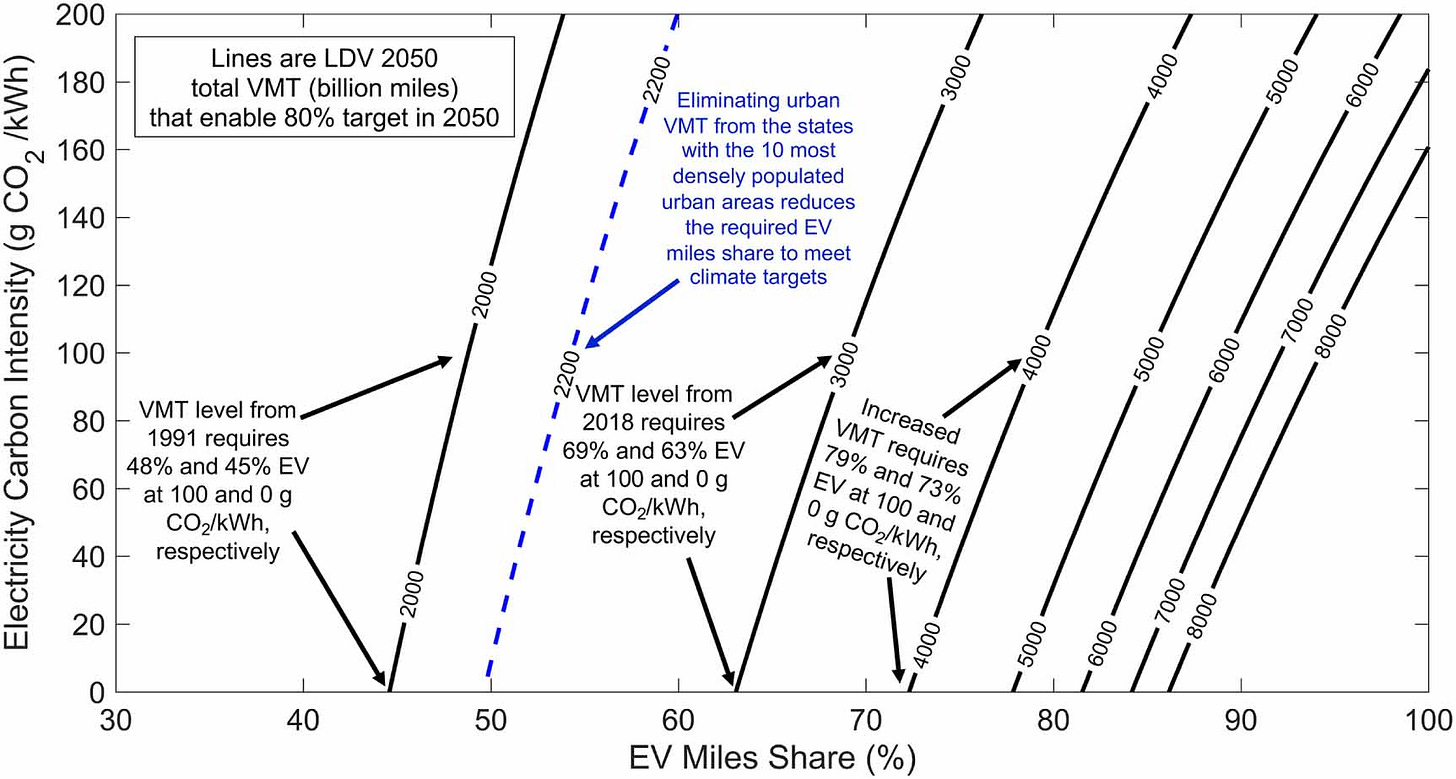

Reducing the number of EVs that we need. The less we drive, and the fewer cars we need, the easier it is to shift our fleet of cars to be entirely electric. The above graph is from Biden White House Economist Costa Samaras, and basically shows how reducing the amount we drive makes it much easier to meet our climate goals. Some good policy levers to accomplish this include:

Improving public transportation. While building a brand new subway is great, it can be expensive. Thankfully, simpler fixes like building more bus lanes and increasing bus frequency have been quite successful in Canada. We need an all-of-the-above approach to improve mobility for those without cars.

E-bikes. E-bikes are a wonderful technology that uses an electric motor to assist a bike, allowing users to go further, faster, and with much less effort (seriously, try one sometime, they’re also super fun). Research has shown that they can replace ~50% of car trips, which would make EV goals much easier to achieve. When I worked in the Senate, I helped introduce the E-Bike Act, which provided a ~$900 tax credit for new e-bike purchases. Unfortunately, this was not included in the Inflation Reduction Act, but many state and local governments are implementing similar programs, and the federal government could do the same if Democrats get the House back in 2024.

Better bike/walking infrastructure. As great as e-bikes are, many people won’t use them if they have to ride on a road with SUVs going 40+ mph. We need protected bike lanes and pleasant streets where people can safely, enjoyable walk to reduce our dependence on cars.

Better land use. Suburban sprawl is one of the top drivers of automobile dependence and increased VMT. As a result, the YIMBY toolkit of building denser housing, clustered around mass transit, is a successful way of reducing car ownership. Some policy levers that can be pulled here include:

Eliminating parking minimums. Parking minimums are unfunded mandates that require any new housing construction to build a certain number of new parking spots. The problem with this is that it drives up the cost of housing (the average new underground parking spot costs over $25,000 to construct), and essentially locks-in car ownership for the life of a building by indirectly subsidizing car owners at the expense of non-car owners.

Upzoning areas near transit. It’s silly that it’s illegal to build dense housing in transit-rich areas, as it artificially constrains the benefits of transit to those who can afford lower-density, more expensive housing. Thankfully, many state lawmakers are cracking down on this exclusionary zoning, with Gov. Hochul in New York leading the way (P.S. You should contact your NY state lawmakers and tell them to support Hochul’s housing plan)

Streamlining dense, transit-oriented housing. Even in places where dense transit-oriented development is legal to build, there are other regulations that make it difficult, including environmental review laws, drawn-out neighborhood appeals, and lengthy permit approval timelines. In California, Scott Wiener has introduced legislation to address this very issue.

At the end of the day, EVs are a net positive for the climate. However, we need smart, targeted policies to maximize the benefits of EVs and reduce the need for automobiles in the first place.

Great writeup Sam! We need to be building up to increase density, and building infrastructure to connect those dense population centers. E-bikes within the city, trains between cities. When we reduce the need for EVs to fewer use cases, we'll see a new wave of interest in car sharing. We need to both accelerate our adoption of EVs, but substantially reduce the number of vehicles on the road.

There’s no advantage to an EV running me over compared to an ICE running me over.