Everything You Need to Know About Inclusionary Zoning

An analysis of the pros and cons of an often-misunderstood housing policy

What is Inclusionary Zoning?

To start with some definitions, exclusionary zoning is the practice of using zoning to make it illegal to build many types of dense housing. For example, “R-1 zoning” is extremely common and mandates that only single-family homes are allowed to be built. Another example of exclusionary zoning is minimum lot sizes that mandate each home must be on a large plot of land. This is exclusionary because single-family homes on large lots use land less efficiently than apartments, raising the average cost of a home and reducing the amount of housing that can be built, especially in high-demand areas with good jobs and schools. This was explicitly done by racist landowners and developers to exclude minorities from wealthy neighborhoods and became more common as outright housing discrimination was banned by Buchanan v. Warley and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Since inclusion is an antonym of exclusion, many people assume inclusionary zoning is the opposite of exclusionary zoning (which would entail getting rid of apartment bans and legalizing denser housing). However, that is not the case. Inclusionary zoning is a specific policy that requires new developments to set aside a certain portion of housing to be rented below market rates. For example, a city with an inclusionary zoning provision might require that any new development has at least 10% of apartments (or 25%, or 50%, etc.) reserved for residents at a certain income level at below-market rates.

Typically, “below market rate” housing is referred to as “affordable” housing, however, “affordability” is a vague term (you could argue that any occupied home is “affordable” because, by definition, someone can afford it), whereas below-market rate clearly notes that the apartment is being rented at a price cheaper than it would be otherwise. Furthermore, there are many types of below-market-rate housing, depending on how heavily it’s subsidized. Some below-market-rate housing is targeted at middle-class people making 80%-120% the median income in an area, and requires a relatively small subsidy, whereas some below-market-rate housing is for those making less than 30% the median income and requires a greater subsidy.

Benefits of Inclusionary Zoning

Now that we’ve covered what exactly inclusionary zoning is, it’s time to look at the pros and cons of the policy:

1. It requires no direct taxpayer subsidy

Since inclusionary zoning puts the burden on developers to set aside a portion of new development to be sold or rented at below-market rate prices, the government itself does not have to spend any money directly to subsidize these apartments. Rather, it functions as an indirect tax on new development, with developers paying for the difference between the market rate and the subsidized rate of an apartment. With ARP funding drying up and municipal budgets no longer flush with cash, this makes it an attractive option for local officials who want affordable housing without compromising funding for other government programs.

2. It promotes integration

Historically, subsidized housing in America has been concentrated in less-desirable neighborhoods, perpetuating cycles of segregation and locking poorer families out of highly desirable neighborhoods that are often safer, closer to good jobs, and have better schools. Inclusionary zoning overcomes this by combining newer, market-rate housing with subsidized below-market-rate housing in the same building.

This isn’t perfect, though. Some developers have built “poor doors”, with different entrances and amenities for below-market-rate tenants. On the whole, though, inclusionary zoning has been better than other policies at integrating neighborhoods and allowing less well-off people the opportunity to live in extremely desirable areas. Another caveat here, though, is that many jurisdictions allow developers to pay a fee for subsidized housing construction elsewhere, instead of building subsidized units on-site.

3. It enables value capture when paired with upzoning

Value capture stems from the fact that upzoning unlocks more value to be created on a single plot of land. A large apartment building provides much more housing for more people (and therefore more value) than a single-family home would on the same plot of land. However, if someone bought a piece of land based on the assumption that it could only be turned into a single-family home, and then a law changed to allow for apartments, that property owner would see their land become more valuable from a government policy change, rather than any work of their own.

Here’s a simplified scenario: say a developer buys a single-family home for $2M; that home is upzoned to allow for 10 apartments that each sell for $500K, and the developer spends $2M on construction. In this scenario, the developer is making a profit of $1M, even though much of that value was created by the public in allowing for denser housing in the first place. However, if an inclusionary zoning provision requires 20% of the apartments to sell for $250K, the developer would only make a profit of $500K with the other $500K of that initial profit essentially returned to the public in the form of two subsidized homes that sell for half of what they otherwise would have.

Downsides of Inclusionary Zoning

While inclusionary zoning clearly has some benefits, it’s not a perfect policy by any means.

1. It can backfire by reducing the amount of housing that is built

Remember the above example of exclusionary zoning? Well, what if the inclusionary zoning requirement was 50% instead of 20%? in that case, the developer would only make $3.75M in revenue ($500K x 5 + $250K x 5), which is less than the $4M cost of acquiring and developing the apartment building. As a result, the building would likely never get built at all, and zero affordable units would be built. The building would stay as is, a luxury single-family home, which seems like a bad outcome for everyone involved. As a result, inclusionary zoning requirements need to thread a fine line, where the percentage requirement is not too high to the point of stifling development. This % amount is different in every city, and even every neighborhood, based on a variety of factors including construction costs, overall market conditions, and other zoning restrictions. In some cities, an inclusionary zoning requirement of even 5% can stifle housing construction, whereas other, more premium markets like San Francisco or New York can often see projects with 20% inclusionary zoning still make financial sense.

2. It can be weaponized in bad faith by NIMBYs

Anti-housing officials and advocates are well aware that inclusionary zoning requirements can make many housing projects unviable. And smart NIMBYs know that elected officials are becoming more dismissive of specious anti-housing arguments around “neighborhood character” and “shadows”. So, they view excessive inclusionary zoning requirements as a popular, socially acceptable way to stop denser housing development. This can be seen in wealthy suburbs like Mamaroneck and Temple City where anti-housing legislators knowingly use excessive inclusionary zoning mandates to block all new housing.

3. It lets existing single-family luxury housing off the hook

At the end of the day, inclusionary zoning is essentially a tax on new housing construction. The problem with this is that we need new housing! New housing is good! From a public policy perspective, it’s best to tax things we want less of (e.g., carbon emissions, smoking, etc.), and subsidize things we want more of (e.g., solar panels). The logic behind inclusionary zoning is essentially the opposite of that, as an existing mansion in Beverly Hills would not be subject to any inclusionary zoning mandate (although, it would be funny if it was; imagine Hollywood celebrities being forced to rent out spare bedrooms in their house at below market rates), while a new apartment building would be. Housing subsidies that relied on broader property taxes across the board, rather than just new housing, would be a more equitable way to fund subsidized housing.

4. Inclusionary zoning relies on a permanent housing shortage

This is a nuanced point, but basically, the idea behind inclusionary zoning is that new housing is so lucrative that developers can afford to set aside a portion of the homes to sell below market rates and still make a comfortable profit. However, the reason that new development can be so lucrative in the first place is that we have a housing shortage. If our goal is housing abundance and broad affordability (rather than the waitlists that inclusionary zoning frequently results in), we would require far more housing construction than we currently have. In this scenario, new supply floods the market, rents go down, along with developer profits, making it so that previously-doable inclusionary zoning requirements no longer pencil out. Inclusionary zoning fundamentally reduces the equilibrium amount of housing that can be built in a market, all other things equal.

My take:

Thinking about the pros and cons of inclusionary zoning, my personal conclusion is inclusionary zoning can be a good short-term housing policy, if it is well designed, but should not distract us from longer-term goals of housing abundance and affordability. Additionally, while the political economy of inclusionary zoning can be favorable due to the lack of need for dedicated funding (and the fact that “affordable housing” sounds good to most residents of liberal cities), simply raising inclusionary zoning requirements without any complimentary pro-housing policy changes can actually result in less housing being built and making an area more unaffordable than it was to begin with.

So, what does a well-designed inclusionary zoning policy look like? Here are some highlights:

Incorporate density bonuses: Density bonuses are a form of inclusionary zoning that acts as a carrot (offering more density in exchange for a certain number of subsidized units) rather than a stick (simply increasing requirements for development).

Streamline permitting and approvals: Unclear permitting processes with long waits, arbitrary requirements, and extensive community input can significantly lengthen the amount of time that it takes to build new homes. Developers are typically looking to start selling housing as quickly as possible so that they can obtain cash flow and pay back lenders, and making permitting quicker lowers costs in a way that can enable more subsidized homes.

Focus on the total number of subsidized homes, not the percentage: When I lived in San Francisco, I frequently heard people say they want to make sure a project is “X% affordable”. However, it’s easy to miss the forest for the trees, and a policy that results in 50% of 1,000 homes being subsidized is less effective than a policy that results in 20% of 10,000 homes being subsidized. And in the case of One45, a development in Manhattan, 50% of 915 apartments being subsidized is better than asking for 100% subsidized and instead getting zero apartments and a big rig truck stop.

However, in the long run, it’s important for state and local governments to look at more holistic approaches to housing affordability. For example, social housing can serve as a housing “public option” that achieves the same type of integration and cross-subsidization as inclusionary requirements, with additional benefits from lower interest rates and exemptions from strict zoning that state and local governments frequently receive. This social housing can serve as an important counter-cyclical alternative to developers who currently face higher interest rates and are more likely to stop building in an economic downturn.

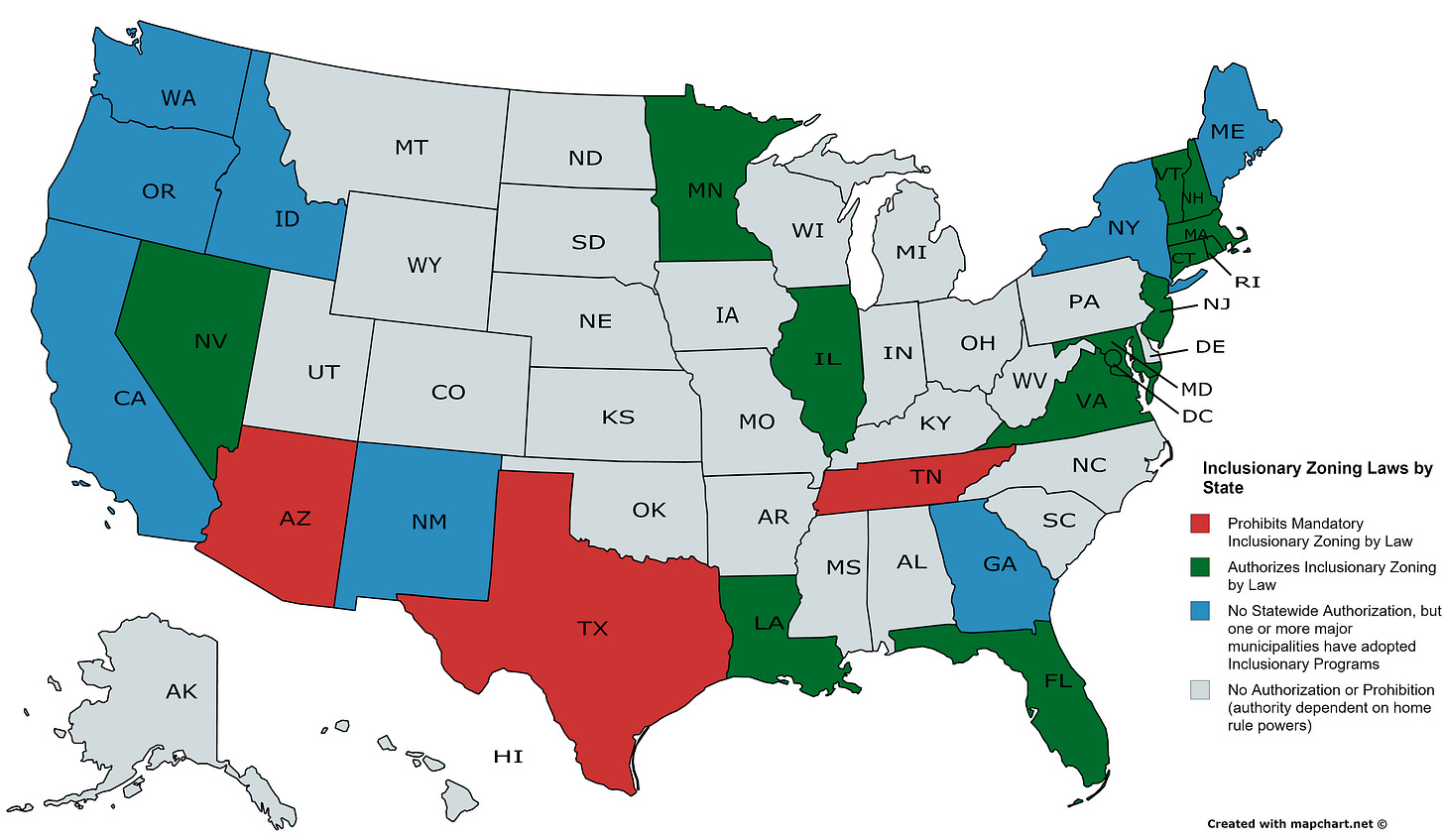

An additional concern that’s worth mentioning is that inclusionary zoning has been banned in some states with conservative governments. Furthermore, The Federalist Society, a right-wing legal group, has argued that inclusionary zoning may be unconstitutional, and given the current makeup of the Supreme Court, I would not be surprised if a case on this ended up nullifying inclusionary zoning across the country. This legal uncertainty is yet another reason why inclusionary zoning should be used as a specific tool, rather than viewed as a silver bullet.

Great post. I really appreciated the detailed pros and cons of the policy.

An additional con: Some places will reserve spaces for more granular income categories like "Extremely Low (30% AMI)" (https://www.smcgov.org/media/126576/download?inline=). I don't know how common this is, but sometimes it's hard to fill the vacancy because it's too low and nobody local qualifies. So, you have apartments that could be used for low or median AMI but remain unoccupied.

Zoning is an excellent opportunity for liberals & conservatives to join forces. Shared interest = thriving communities.

Start the conversation with "abolish zoning" to shift the Overton window towards more diverse, affordable, practical, and healthy neighborhoods.