A few weeks ago, I was helping one of my friends move into Manhattan. We were driving his stuff into the city in a rental car, and the experience was eye-opening. I never drive into Lower Manhattan (because the subway/walking/citibike is cheaper, more convenient, and more pleasant), so experiencing it first-hand made me realize just how beneficial congestion pricing would be.

The traffic was truly absurd. There was essentially total gridlock as we drove up 3rd Ave to the Queens Midtown Tunnel. Going half a mile from 24th Street to 34th Street took about half an hour. You could walk 3x as fast. We were literally going one mile per hour. The status quo of gridlock in Lower Manhattan is unacceptable, and congestion pricing is the only real way to fix it. This explainer will dive into just exactly how congestion pricing will benefit everyone in New York City, even drivers.

What exactly is congestion pricing anyway?

Congestion pricing is based on a relatively simple economic idea: the supply of roads in Manhattan is more or less fixed - despite Robert Moses’ best efforts, nobody is building a cross-Manhattan highway anytime soon. However, the demand for road space is quite high - as evidenced by the gridlock that the city experiences every single day. The gridlock hurts everyone: drivers don’t want to be stuck in traffic, but since road space is not accurately priced, the amount of cars in New York City exceeds the supply of road space. This manifests itself in gridlock. It’s a well-understood facet of supply and demand: when you underprice something to the point that demand outstrips supply, people will form lines, whether it’s bread lines or people waiting in line for hours when Sheetz lowered the price of gas to $1.776 on July 4th. Congestion pricing acknowledges this reality and will charge drivers between $9 and $23 to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street by taking pictures of their license plates and sending them tolls. Some drivers will say “that’s not worth it to me” and find alternatives like the abundant transit options in lower Manhattan, reducing the amount of gridlock for everyone else.

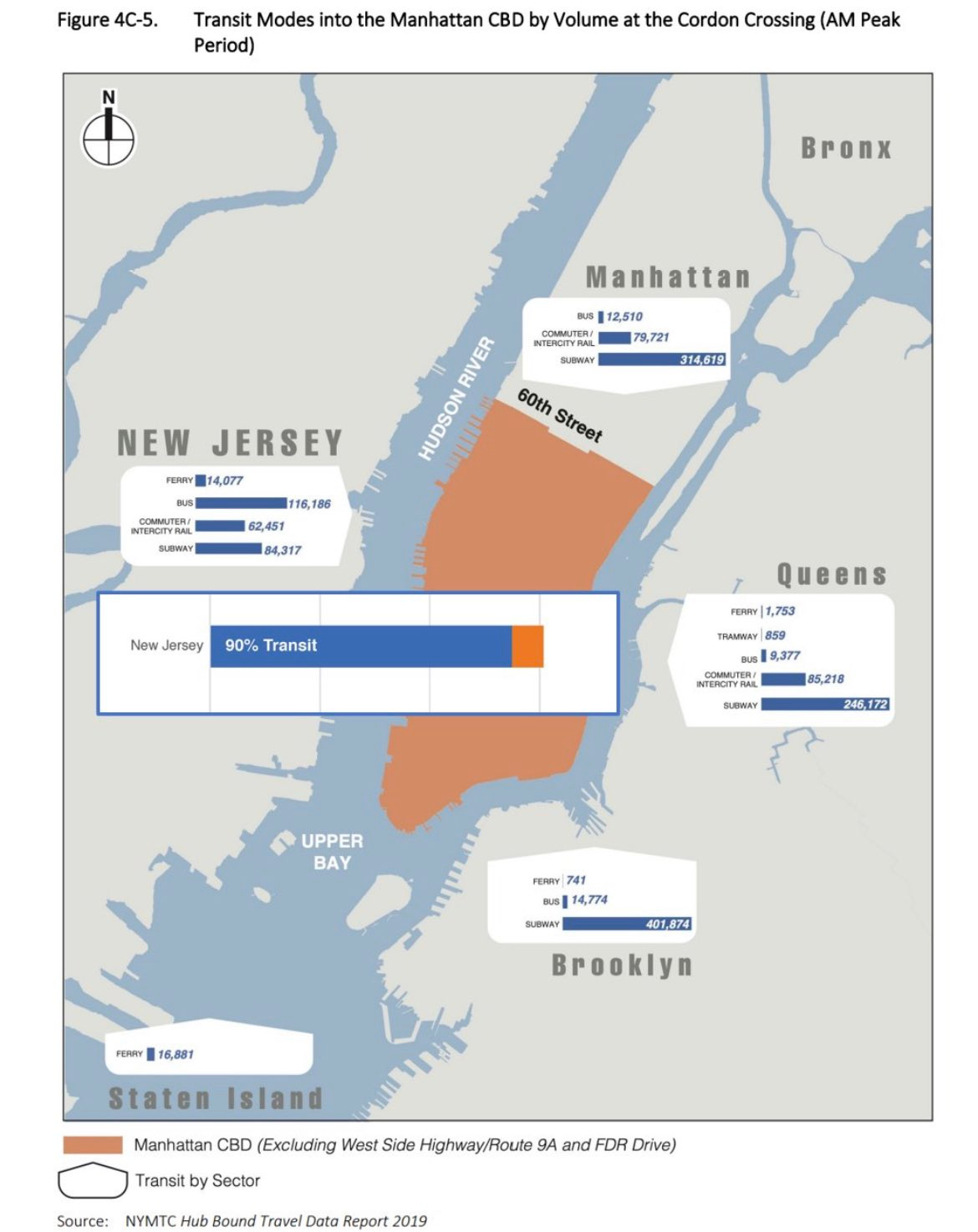

While this seems like a common-sense policy, it has provoked a lot of backlash. Primarily, this opposition has been from New Jersey politicians who have filed a lawsuit to stop congestion pricing. However, most of the arguments that these politicians make are in bad faith, and (almost) everyone is better off with congestion pricing. Before I get into the details, I also think it’s worth really hammering one fact: Manhattan has the best transit network in the entire country and the overwhelming majority of people entering the congestion charging zone take transit.

Let’s break it down:

Winner 1: Air Quality

Congestion pricing has been shown to improve air quality in the cities across the world where it has been implemented. This makes sense because congestion pricing reduces driving, which is a top source of air pollution. In London, a recent medical study showed that the air quality improvements stemming from congestion pricing had substantial mortality benefits. To put it simply - congestion pricing saves lives. A recent study in Stockholm confirmed this, finding that the city’s congestion charge reduced air pollution by 5-15%, translating into fewer acute asthma attacks among young children. The initial studies of New York’s congestion charge expect the same outcome: reduced pollution across the city. And that’s important because evidence continues to mount that air pollution is really, really bad for you, with a host of negative impacts ranging from birth defects to asthma to decreased learning ability and productivity.

Winner 2: The MTA and anyone who takes transit in New York City

Congestion pricing is expected to bring in $1 billion annually for the MTA, of which 80% will go to improving the subway and buses, 10% will go to Metro North, and 10% will go to the LIRR. All of the money is being used to improve transit and improve options for the overwhelming majority of people in the city who rely on transit every day. And despite the recent 15 cent fare increase, transit fares are still well below where they were 5 years ago when adjusting for inflation, and congestion pricing will help reduce the need for future fare increases. But the benefits don’t just stop there: by reducing the amount of congestion, buses will travel faster and more efficiently, improving service frequency and speed.

It’s also worth noting here that the overwhelming majority of commuters into Manhattan already take some form of transit, with a recent MTA study finding that less than 20% of all workers in Manhattan drive to work. Furthermore, even in New Jersey, which has been the hub of opposition to congestion pricing, only 52,000 people drove to work compared to 256,000 who took some form of public transportation. It’s always important to keep this scale in mind: the overwhelming majority of people getting around in lower Manhattan do not use cars.

Winner 3: Pedestrians and Bikers

I live in Chelsea and frequently walk through the city, and the cars are such a pain. They are loud, causing noise pollution, which is increasingly shown to be a real health hazard. They also get in the way, blocking intersections illegally when pedestrians and cyclists are trying to cross. This slows down and inconveniences bikers and pedestrians, and can be dangerous by forcing them into the middle of traffic. I have also personally experienced just how aggressive New York drivers can be, and having fewer of them on the road would drastically improve the quality of life for people in the city. Finally, congestion pricing will help New York City accomplish its Vision Zero goals by getting dangerous cars off the road, which I recently wrote about.

Winner 4: The Climate

Cars are one of the top sources of carbon emissions that contribute to climate change. In addition to reducing particulate emissions, congestion pricing will also reduce carbon emissions, and previous studies have found that congestion pricing can reduce transportation emissions by 22% relative to the status quo. People will drive less and carbon emissions will go down. It’s not that complicated.

Winner 5: People in Emergencies

Nothing pains me more than seeing an ambulance or fire truck with its sirens on stuck in gridlock. In these emergencies where every second could be the difference between life and death, it’s absurd for these life-saving first responders to be stuck in traffic behind a suburbanite who drove into the city to see a Broadway show. It’s a horrible inefficiency that costs lives, but it doesn’t have to be that way: successfully implementing congestion pricing will reduce the gridlock and save lives by reducing emergency response times. Even the FDNY has already said that traffic (not bike lanes) is slowing down their response times.

Winner 6: People who have to drive

Some people have to drive into New York City. Whether it was me helping my friend move, a contractor who needs to bring a truck full of tools, or delivery drivers, we are never going to have a completely car-free city. However, congestion pricing helps all of these people. When me and my friend were stuck in traffic, we would have happily paid 20 dollars to save 30 minutes of time just stuck in gridlock. Additionally, people who need to drive will have another reason to carpool and save money on gas, congestion charges, and parking, all while dealing with less traffic. The argument is even stronger for delivery contractors who spend all day working in the city and often charge rates that start at $50/hr (the guy who installed my TV charged $100/hr). Since many of these trucks have two occupants, saving 30 minutes of time translates into over $50 of value saved in the form of a shorter commute or being able to do an extra job. Suddenly, paying $20 for reduced congestion seems like a pretty good deal. The argument is even stronger still for delivery trucks who will now be able to deliver far more packages/goods and make more stops by avoiding traffic. This could help reduce delivery fees for small businesses and restaurants as well.

Additional Debunking:

There’s lots of false or misleading claims against congestion pricing that are worth quickly addressing:

Myth 1: Poor people make up the majority of people driving into Manhattan. That’s not true. The people who do choose to drive into Manhattan are, on average, wealthier than those who take transit. This makes sense: car ownership is expensive and parking a car in Manhattan isn’t cheap either.

Myth 2: This is an unfair attack on the sovreignty of New Jersey. New Jersey already tolls people on their highways. The New Jersey Turnpike has some of the highest tolls in the country. States have long had the right to toll cars on its roads. If New Jersey wishes to raise its own tolls in response to congestion pricing, I say go right ahead.

Myth 3: This wasn’t studied enough/was rushed through. Insurrectionist Staten Island congresswoman Nicole Malliotakis is complaining that the environmental review of congestion pricing was rushed through. This is false and the reality is the opposite: congestion pricing has been under study for four years at this point and the MTA recently issued a 4,000 page report on it. If you want to learn more about this, I wrote about how America has the opposite problem: it takes us way too long to do good things like congestion pricing or build transit/renewable energy because of outdated environmental review laws like NEPA.

Myth 4: Congestion pricing will hurt the economy. This is false, and as I detailed above, it will actually improve productivity of deliveries and contractors who need a car to get around. A recent study actually found that New York’s congestion costs the city $20 billion every single year due to lost productivity, wasted fuel costs, and higher costs of doing business. And that doesn’t even include the additional billions in detrimental health and environmental effects of congestion.

Myth 5: Cars already pay their fair share and aren't subsidized. Many people think that the gas tax and tolls fully cover the cost of road construction and maintenance. This is false. On average, gas taxes and tolls only cover about half of road spending in America. New York is slightly higher at a little less than two-thirds, but still, that means that the rest of road funding is from taxes that everyone, even non-drivers pay. The gas tax hasn’t been raised in 30 years, and subsidies for drivers are increasing. The subsidies are even bigger when you factor in parking. New York City has approximately three million street parking spots, and 95% of them are free. Given the value of land in New York City, this translates to billions of dollars in subsidy for drivers at the expense of everyone else in the city. And again, all of this is before considering the massive social costs of pollution and carbon emissions.

It’s also worth calling out the bad faith arguments of New Jersey politicians who say that congestion pricing will increase emissions in New Jersey (most studies show it will have a negligible effect on New Jersey pollution, and if anything it will broadly reduce pollution across the tri-state area as drivers switch to transit) even as they support a $11 billion highway expansion that is guaranteed to increase pollution in Jersey City. If Josh Gottheiemer and Phil Murphy truly cared about pollution, they would be fighting to improve NJ Transit instead.

How can we make congestion pricing even better?

This isn’t to say New York’s congestion pricing plan is perfect. As with any good policy, there are ways it can be improved even further. Some big ones are:

Use some of the congestion pricing revenue to improve New Jersey’s transit options. It’s great that the revenue is going to improve the subways, LIRR, and Metro North, but there should also be increased funding for better transit service across the Hudson via PATH and NJTransit. New Jersey politicians should drop their adversarial anti-congestion pricing stance and instead come to the table and find ways to turn this into a win-win.

Build transit more efficiently. The billions of dollars from congestion pricing should be used to build as much transit as possible. The increased funding is great but it should go as far as possible. I recently wrote about reforms the MTA could make to build transit more efficiently, and now would be a great time for the agency to start implementing them.

Build more transit-oriented housing. Congestion pricing is essentially the state of New York saying “we have great transit, and we want as many people as possible to use it instead of driving”. Which just heightens the ridiculousness of exclusionary zoning and parking minimums near transit in most of the state. The state legislature needs to adopt the pro-housing measures that Gov. Hochul has been pushing in order to ensure that more people can live near transit.

Ensure that congestion pricing is dynamic. The exact details of congestion pricing haven’t been hammered out yet, but a common-sense policy under consideration would be to adjust the price paid by the amount of traffic based on live data. Someone driving into the city at 2AM when there’s very little traffic should pay less than someone driving into the city at 8AM during rush hour. Additionally, there should be a way to have additional congestion surcharges for loud, excessively large trucks that take up more road space and cause more pollution

Expand it! One of the things I’m most excited about with congestion pricing is that it will be a resounding success and soon neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Queens will be asking for congestion charging of their own. Additionally, other cities such as San Francisco, Boston, Los Angeles, Washington DC, and Chicago have been “studying” congestion pricing for years, and a successful implementation in New York could be exactly what’s needed to turn those plans into reality.

Finally, congestion pricing is an extremely easy policy to change - there’s very little permanent physical infrastructure required (just some cameras), so I hope the MTA continues to tinker and experiment with how to improve it.

At the end of the day, cars are extremely bad for the environment, our lungs, our personal safety, and our use of space, with some studies suggesting a $80 congestion fee would be needed to fully account for those external costs of driving a car in Manhattan. But the MTA’s congestion pricing is a great start, and I greatly look forward to it coming online next spring.

Myth 5: Cars already pay their fair share and aren't subsidized

It's mind-boggling how common this one is given how totally false, but systems of accounting makes it easy. It's used as a justification for "Why use congestion charge to fund transit which loses money?".

In reality, cars are heavily subsidized, especially in New York City.

* I estimate the value of roadway below 60th St at 100 mil sq ft. (seems like a lot, but only 4 sq miles.). But at $2,000/sq ft, 100 mil sq ft is worth $200 billion. At 5% interest/land rent equivalence, that single implicit subsidy is worth $10 billion per year. MTA has to pay for land when it buys it and keep it on the balance sheet.

* The health effects of vehicle emissions. I'm not qualified to put a number on this. Across a wider area like New York though this has been estimated at $20 billion/year.

* Noise pollution costs. The ratio of bad reasons compared to good reasons for honking in NYC is incredibly high. Sirens run for longer because they are stuck in traffic.

It's a myth to consider the $3 billion / yr budget for capital and operations for roadways in NYC as being a complete accounting of the public costs of vehicle use. That's really only a fraction of the cost if it received none of the implicit subsidies.

Gasoline taxes for NY State ($1 billion/yr) aren't even enough to pay for the explicit spending by the city, much less enough to pay for the much larger hidden subsidies.

Fantastic article Sam.

For the FDNY mention I think you meant to link here? https://nyc.streetsblog.org/2019/09/19/fdny-traffic-not-bike-lanes-is-to-blame-for-increased-response-times