America's Infrastructure Costs are Too Damn High

And it's stopping us from addressing climate change

As I write this, I am traveling 190mph on a high-speed train from Madrid to Barcelona. My ticket was $20. Trains leave every 15 minutes. It is quiet, smooth, direct, and pleasant, far more than flying.

Throughout my time in Spain, I asked myself why the infrastructure is so much more advanced than in America despite having ~40% of the GDP/capita as the US. In the past 30 years, Spain has built over 2,000 miles of high-speed rail, significantly reducing the number of local flights. Meanwhile, America has built only the Acela, a “high-speed rail” from DC-Boston that can only go 150mph, and in reality averages under 70mph due to a lack of straight track. The total DC-BOS trip takes ~7 hours. If Acela went as fast as the Madrid-Barcelona train, it would be ~3 hours, more than twice as quick as it is now.

So, why can’t America have nice things? Part of it is funding - yes, we should absolutely be investing more in transit and high-speed rail. But the other side of the equation is the costs: we get disturbingly low bang for our buck on infrastructure spending. The recent bipartisan infrastructure bill contains 66 billion dollars in Amtrak funding. Given the fact that Spain built 2,000 miles of high-speed rail for about the same cost, the Amtrak funding should be enough to at least turn the ~450 mile Northeast Corridor into a real high-speed rail line, right? Nope. A recent Amtrak proposal instead found that would cost 117 billion… and it still wouldn’t be as fast as Spain’s high-speed rail. I cannot stress enough how abnormal America’s construction costs are, and bringing these costs down to normal levels relative to peer countries is an absolute necessity if we want infrastructure that is sustainable, efficient, and convenient. I’ve already written about how EVs are not enough to meet our climate goals and create safer roads. But the primary alternative to EVs is transit, and in order to shift people from cars to transit, we have to build a ton of transit.

How bad are our infrastructure costs, really?

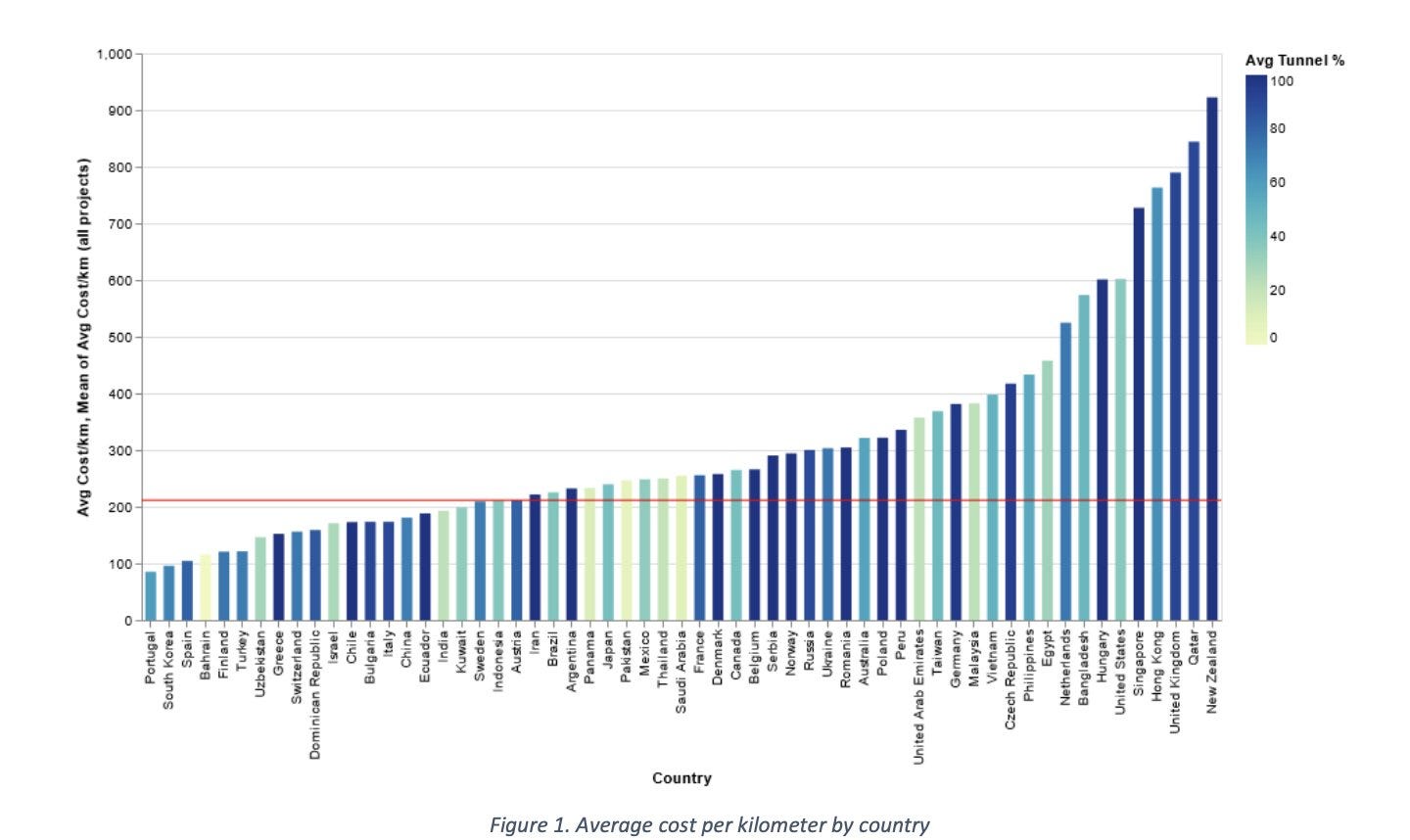

They’re bad. But it’s worth emphasizing just how bad they are. We’re not talking 50% more expensive than other developed countries. We’re not talking 3x as expensive. Nope, the US is often 10x more expensive than comparable developed countries.

This graph makes America look bad, but when you get into the details it’s even worse: most American rail construction is above-ground light rail, which is inherently cheaper than below-ground subways being built in the UK or Singapore. To get an apples-to-apples comparison, a below-ground subway currently being explored is Phase 2 of the Second Avenue Subway in New York, where the projected cost is $7.7 billion for 2.4 kilometers of subway That’s $3.2 billion/KM, more than triple the cost of building in the most expensive country in the world (New Zealand) and approximately 30x as expensive as Spain, South Korea, or Finland.

What does this look like in practice? It means that we simply are unable to build the infrastructure we need, even when voters support funding transit. Here are some recent examples of excessive infrastructure costs hindering American transit projects:

Austin: Voters approved a multi-billion transit program called Project Connect, increasing property taxes to build a comprehensive rail network with tunnels downtown. Due to rising construction costs, transit proposals have been scaled back significantly.

Atlanta: Voters approved a sales tax increase that would raise $2.7B to drastically increase public transit. Due to increasing costs, light rail has been scaled back to bus rapid transit, and only 9 out of the 17 initial projects are moving forward. Residents are unhappy that the promised transit improvements they voted for are not coming to fruition.

Philadelphia: A proposed rail line to King of Prussia, a Philadelphia suburb, was halted due to ballooning costs. The Federal Transit Administration refused to fund the project due to these increasing cost overruns. The projected price for this aboveground, 4-mile rail project was over $3 billion despite projecting to have only 10,000 riders. As a fun/sad point of contrast, the Italian city of Turin is currently constructing a 17-mile, 32-station, completely automated driverless metro for a similar ~$3B price tag that would serve ~300,000 passengers per day.

New York: A proposed AirTrain connecting LaGuardia Airport to the New York City Subway was recently scrapped after costs inflated fivefold from an initial estimate of $450 million to $2.4 billion. More concerning is that a better way to connect LGA to NYC is by extending the N/W subway instead of an “AirTrain” people mover. However, the extreme costs made the project infeasible, with the proposed 2-mile subway extension projected to cost $7 billion, funding that the MTA doesn’t have. Again, Turin is building a 17-mile, fully automated metro line for half the cost as this 2-mile spur would be. It’s absurd.

All of these issues come back to the fact that when governments approve transit funding, there isn’t some magical unlimited money spigot. Rather, it’s usually a combination of local and federal funds. Local funds are capped by politically-feasible tax increases and bond issuances, while federal funds are competitive and limited by Congressional appropriations. So when transit costs increase, we don’t just get more expensive transit, we get less transit. A lot less transit. This creates a political death spiral: if people vote to increase their taxes to fund a transit network, but the transit network ends up being a fraction of what was promised, guess what - voters are more likely to reject future taxes to fund transit! And people just end up driving, stuck in ever-worsening traffic. We really need to get our construction costs under control. So, how can we do that?

What’s causing our sky-high transit costs and how do we fix it?

There have been two great reports released recently examining why American construction costs are so high, from transit policy think tank EnoTrans and NYU’s Transit Costs Project. These reports are ~200 and ~400 pages, respectively and I read them so you don’t have to. Some of the key takeaways on the reasons (and solutions) for our sky-high transit costs are:

Overbuilding station sizes. Over three-quarters of the Second Avenue Subway's hard costs are the stations, rather than the tunnels, and the station lengths are more than twice as long as the platform. This is in contrast to other countries where station lengths are only 3-20% as long as the platform.1 Furthermore, the Second Avenue Subway features large, unnecessary mezzanines above the platform that primarily serve an aesthetic value rather than a functional one. Solution: Build smaller stations with fewer mezzanines.

Excessive focus on minimizing any above-ground disruption. Having lived in San Francisco for a couple of years, I frequently took BART to the East Bay and noticed that the trains would slow to a crawl for a few minutes in Oakland, due to an extremely sharp turn. Why? The mayor of Oakland in the 1960’s, John Houlihan, had a friend who owned a hardware store on 8th St. and refused to support BART unless they redesigned the system to go under 9th St., requiring a sharper turn. The worst part of this story? The hardware store went out of business anyway six months later. Despite the hardware store being long gone, passengers have had to deal with slowdowns on this section of BART every day for 50+ years. This is just one example of politicians prioritizing short-term minimization of above-ground disruptions even when the long-term transit disruption is infinitely greater. Another example of this short-sighted practice is currently underway in San Jose, where BART is building a six-mile subway extension projected to cost ~$10B and be constructed six stories underground to avoid disrupting aboveground stores, even though it is much more expensive and will be a major inconvenience to future passengers. Given the billions being spent on this project, it would be far more cost-efficient to simply pay out local businesses to make up for lost revenue while construction is underway. Solution: Embrace cut-and-cover and other efficient transit construction techniques and use the cost savings to compensate for any above-ground disruptions.

Lack of standardized designs. In the US, most transit stations have unique designs preventing economies of scale, since each station needs to be specially designed with unique contractors, parts, and equipment. In countries with cheaper construction costs, they standardize as much as possible, and I personally noticed this in Madrid where most of the subway stations had similar designs. As a result, a recent Madrid Metro expansion for Line 9 cost less than $100m/km2. Solution: Standardize station design wherever possible rather than building overly-complex bespoke stations.

Poor contracting and lack of clear costs for individual line items. In low-cost countries like Turkey, Spain, and Italy, agencies have official benchmark prices for most items that are used in constructing transit infrastructure. This increases transparency and lowers costs by disseminating this knowledge across the agency and improving the ability to hold contractors accountable by reducing change order disputes. However, NYC lacks this data in any systematized, central way, and major American contractor Tutor Perini is known as the “change order king” for infamously low-balling projects and then using change orders to significantly raise the price of construction3. Solution: Develop universal, transparent line-item costs and award contracts based on technical merit rather than the lowest price.

Lack of curiosity amongst elected officials and transit agency heads. Transit agencies can be weirdly hostile to accepting the fact that there is even a problem with construction costs to begin with. Recently, Janno Lieber, the head of the MTA, dismissed people concerned about transit costs as “A subculture… that gets a lot of their cost information from the internet.” In one sense, Janno is right-it is pretty absurd that most of this research is coming from external think-tanks and academics rather than the government itself. But that’s because the government isn’t investing in this type of research on its own. Beyond the EnoTrans and Transit Costs Projects reports (both of which came out in the past couple of years), there’s been surprisingly little research into why America has fallen so far behind in infrastructure construction. Given the hundreds of billions being spent on American transportation, spending a few million dollars to evaluate best practices seems like a no-brainer that would easily pay for itself. Ideally, the FTA would staff experts with international expertise who could provide advice to local agencies. Furthermore, American agencies should look internationally to hire employees and leaders who were successful at running international transit agencies that are far more efficient than ours. It’s no coincidence that the best head of the NYC Subways was Andy Byford, a Brit. More broadly, American agencies should develop long-term knowledge-sharing partnerships with global agencies that are doing things right. There’s some good news here, though: the MTA actually took heed of many of these recommendations and saved $1.3 billion in its design for the Second Avenue Subway! The research on bringing down costs has incredible ROI. Solution: We need to hold transit agencies accountable for their cost overruns. That means forming advocacy groups and lobbying elected officials to acknowledge the problem and putting political pressure on transit agencies to fix it. Additionally, the US should invest federal funding into transit research to serve as a resource for municipal agencies, hire more international employees, and develop international partnerships.

Disconnect between housing and transit planning. Some of the most successful transit agencies in the world make money by buying real estate near future transit lines, constructing dense mixed-use buildings, and renting them out. Specifically, France, Italy, Japan, and Spain all have combined ministries that link housing and transportation investments. Typically, transit construction raises real estate prices by serving as an amenity. It’s a no-brainer for transit agencies to capture that increased value by engaging in real-estate development. More broadly, building more densely near transit improves ridership and therefore farebox revenue for transit agencies. While this isn’t directly related to infrastructure construction, it would broadly help transit agencies pull in fare revenue. Solution: The US should increase coordination between HUD and DOT and enact federal incentives for legalizing more housing near transit construction such as the Build More Housing Near Transit Act.

Labor inefficiency. While many assume that unions and high wages are what drive up labor costs, the situation is more complex, as Stockholm and Paris both have much lower labor costs despite having extremely strong unions and high wages4. Rather, the problem is labor inefficiency. For example, the Second Avenue Subway had 46 employees operating a tunnel boring machine, compared to an average of 30 employees in Europe. American unions play a role in this as well, by bringing a zero-sum mindset to many issues, in contrast to European unions that are willing to share in the cost savings that come with efficiency gains. In most of the world, subways have one-person train operation (OPTO), with one operator who drives the train and handles the door opening/closing. However, New York City unions are fighting tooth-and-nail against this, even though OPTO could help ease staff shortages and instead of resulting in layoffs, could serve as a fantastic talent pool for operating more trains and buses. Solution: Politicians and unions should be more flexible in negotiations and seek out win-win solutions that increase worker efficiency, productivity, and service.

Lack of flexibility and coordination across agencies. American government agencies do not do a good job of efficiently communicating with each other on issues like utilities where a transit agency needs to work with a local department of water & power. For example, the MTA spent a quarter billion on agreements with other agencies and utilities to get permits to dig the Second Avenue subway5. In contrast, Milan has one agency build both metro tunnels along with other city utilities which makes coordination far quicker and simpler6. Solution: Have dedicated employees across government utilities who are empowered to coordinate with transit agencies efficiently.

Shortage of skilled in-house workers and overreliance on external engineering contractors. In Boston, the cost of the 7 kilometer Green Line Extension was initially projected to be $1.12 billion. However, only 5 MBTA employees were reported to be working on the project full-time7, giving the agency a lack of expertise to manage such a large project due to budget cuts in the 1990's under Gov. Weld and then-budget director Charlie Baker. As a result, costs basically doubled, and the MBTA spent a quarter billion alone on project management contractors rather than managing the project itself for much cheaper. Furthermore, the lack of in-house staff made oversight more difficult, resulting in delays in contract approvals8. While the MBTA eventually staffed up to address these issues, the short-staffed nature of the agency caused delays and cost increases. The same could be seen in New York when the MTA spent $656 million on contractors to design and engineer the Second Avenue subway9. Solution: Ensure that transit agencies have the budget and flexibility to hire employees to manage projects in-house. While in-house employees may cost more up-front, they pay for themselves in reduced costs long-term10

Excessive “environmental review” process. As I wrote in my past substack article, many environmental review laws are weaponized to slow down transit and increase costs. It’s absurd that a highway and a transit line should be subject to the same level of environmental review when transit reduces emissions and highways increase emissions. Where I grew up in Maryland, NEPA (the federal environmental review law) gave rich homeowners the ability to sue and stop the project, claiming that there was a rare microscopic fish that only existed in a spring near the proposed train tracks. A scientist spent a week looking through the entire path and found that the microscopic fish in question never existed. In contrast, Madrid has a specialized, streamlined environmental review process for transit11. Solution: Reform NEPA to ensure that climate-friendly projects like transit have a streamlined review process that is exempt from frivolous NIMBY lawsuits

Counterproductive “Buy America” provisions. “Buy America” is a rule that all “steel, iron, and manufactured goods” in a transit project must be produced in the US12. While this often increases costs due to more expensive products (a 2011 study found that Buy America increased highway construction costs by $652M annually13), the bigger issue is that compliance is often extremely time-consuming for transit agencies due to a lack of American-made products for extremely-niche functions. For example, the Second Avenue Subway was delayed over confusion on whether a fire suppression system made in Finland was compliant14, and eventually the fire system had to be removed and replaced with an American one. While there is understandable concern over outsourcing infrastructure competition to our geopolitical rivals, Buy America doesn't even address that well. For example, Buy America still allows the MBTA to use CRRC, a Chinese state-owned company for subway cars, as long as the final assembly takes place in the US. This has become a total boondoggle, with the trains being poorly constructed and having a host of issues preventing them from going into service. Solution: Reform Buy America to allow the purchase of equipment from our allies and make it easier for agencies to comply

Believing the hype of boondoggles. The hyperloop is a grift pushed by Elon Musk to kill high-speed rail. The Boring company Tesla tunnels are a scam. And yet, many local government agencies are wasting their time and money on these doomed projects (like Chicago working with the Boring Company for a tunnel to the airport). It could be argued that this is a symptom of our expensive transit costs - agencies are thinking creatively to find alternative solutions. The problem is that the alternative solutions (like hydrogen trains) don’t work as well as tried-and-true solutions like electrifying trains with overhead catenary. Solution: Transit agencies should spend less time “innovating” by trying to reinvent the wheel and instead spend more time copying best practices that have seen international success.

At the end of the day, America’s failure to build transit infrastructure is one of the biggest barriers holding America from achieving our climate goals. We are the wealthiest country in the world, if we can get costs down to internationally comparable levels, we can go on an incredible building spree to rebuild our country around mass transit and high-speed rail that makes America more dynamic, equitable, and sustainable.

TCP Page 13

Eno Page 81

TCP Page 29

TCP Page 32

TCP Page 349

TCP Page 30

TCP Page 49

TCP Page 52

TCP Page 363

Eno Page 43

Eno Page 9

Eno Page 71

Platzer and Mallett, 2019 cites: Gary Clyde Hufbauer, and others, Local Content Requirements: A Global Problem, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2013.

Federal Transit Administration, “Buy America Investigation Decision: Second Avenue Subway Project’s Water Mist Fire Suppression System,” January 6, 2015.

Our infrastructure costs in the US are another example of being distracted by the "needs" of corporations and the wealthy. If we focused on the issues, you've shown that this a solvable problem that will have exponential returns for generations to come. We need to get out of our own way.

These costs for infrastructure are staggering. I’m trying to parse the differences between permitting timeline costs (government reviews) and construction costs (productivity). In my own experience the cost of construction is tied to the relative lack of competition at all levels of construction from the Construction Managers to the sub contractors. This works is so relatively rare and specialized and the specification are so detailed that the same participants show up every time. Costs only increase in that rarefied environment.