When people think about carbon emissions from housing, most of the discussion is at the micro scale: “is this building LEED-certified?” “does that building have solar panels”, etc.

However, we need to look more at the climate impacts of housing at the macro level. And to do that we need to look at housing policy, and how that influences consumption and emission patterns more broadly.

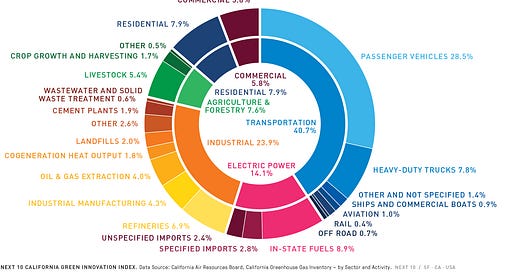

The above graph is a perfect illustration of that. While “residential” greenhouse gas emissions are only 7.9% of California emissions, housing patterns greatly influence passenger transport, which is responsible for an additional 28.5% of emissions, and electric power consumption, which is responsible for another 14.1% of emissions. As a result, housing directly touches about 50% of all carbon emissions in California. In this post, I will break down exactly what this looks like and identify housing policies that can drastically reduce carbon emissions.

Direct Household Energy Use

Direct energy use is the most commonly thought-of energy use at the housing level, which makes sense because it’s the largest source of direct residential carbon emissions. More than half of at-home energy usage in the US is for heating and cooling, with heating (and water heating) being highly energy intensive as can be seen in the below graph.

More broadly, I’ve noticed a common misconception that hot climates are worse for the environment due to requiring A/C, but in reality, cold-weather climates are typically even worse for carbon emissions for two reasons: The first being that most A/C is powered by electricity while many cold-weather heating systems are powered by less-efficient oil heating systems. The second reason is even simpler - using a comfortable 72-degree baseline, cold winter weather (30 degrees) is simply further from that baseline of 72 than hot weather (90 degrees), and therefore requires more energy to adjust the temperature.

Some of the policy recommendations here are obvious and included in the IRA (if you’re reading this you should probably look into applying for these credits and making your home more sustainable):

Subsidize heat pumps to replace gas furnaces, which can reduce emissions by over 50% in the short term, and even more in the long term as the grid is decarbonized and the energy used gets even cleaner.

Subsidize residential clean energy production, particularly solar and geothermal

Improve the efficiency of existing houses with better insulation

However, this is just the start. We need to holistically look at what we are building. And what policies can help us build better. Specifically, we need to be building more apartment buildings because they are inherently more energy efficient than single-family homes. As seen below, apartment buildings with more than 5 units average around 1/3rd as much energy consumption as a single-family home. The lower energy usage is due to the fact that apartments are typically smaller than single-family homes and that apartments have shared walls, reducing exposure to exterior temperatures and resulting in less energy loss. Additionally, apartment buildings are getting more efficient due to the scalability of energy-saving techniques such as new insulation and more efficient HVAC systems, while single-family homes are getting larger, and therefore less efficient.

Despite the climate benefits of dense housing, many cities have restrictions on multi-family housing via height restrictions, density restrictions, apartment bans, parking mandates, and other forms of exclusionary zoning, and government officials should look at repealing the laws that make these apartments difficult or impossible to build in much of the country.

Transportation

Even though carbon emissions from transportation are not directly included in housing climate emissions, it is impossible to disentangle the two. As shown in the earlier chart, passenger vehicles account for 28.5% of all carbon emissions in California, making it the largest single source of emissions in the state. This connects to housing because where we build housing largely influences how much people drive.

On a global scale, the US is far behind other developed nations, averaging ~13,000 KM vehicle miles traveled per capita, approximately twice as much as western Europe (~6,500 KM) and more than three times as much as Japan (~4,000 KM), which can be largely attributed to America’s uniquely low-density, sprawling housing stock.

This can be further seen when looking at the individual city level. Looking at New York City, the inner urban area has extremely low transportation carbon emissions due to the prevalence of mass transit and low rates of car ownership. However, once you get out to the suburbs you see much higher rates of transportation carbon emissions due to longer commutes and housing density that is too low to sustain mass transit usage. The IPCC agrees, noting that “increases in urban density can effectively reduce per capita car use by reducing the number of trips and shortening travel distances”.

America’s focus on building car-oriented environments over the past hundred years has contributed greatly to our carbon emissions, to the point where Texas roadways alone have contributed to 175MMT of CO2/year , while Germany (with a more than 3x greater population than Texas) is only emitting 148MMT of CO2/year . Texas is emitting about 4x as much carbon emissions per capita on its roadways as Germany, which can largely be attributed to the car-first urban planning in Texas, where most cities have low-density zoning and parking minimums that legally mandate new developments to build parking.

Another example can be seen in the above chart, where even though Atlanta and Barcelona have similar populations, Atlanta has 9x higher transportation energy per capita. Even though Atlanta has 77 kilometers of subway, it only gets ~90K riders every day since the spread-out nature of the city naturally disincentivizes mass transit. Meanwhile, Barcelona has 125 kilometers of subway but gets ~800K riders every day, benefitting from the large, compact nature of the city.

Since low-density suburban sprawl requires much more land to house the name number of people as a denser urban area, new low-density suburban subdivisions often require bulldozing forests, with a recent US Forest Service report finding that 34 million acres of forest are at risk as expanding sprawl requires more land. Additionally, lower-density land use requires less efficient and more spread-out usage of services such as garbage collection, sewage lines, electricity lines, etc. This means that less dense homes require more resources and a recent study found that sprawling areas impose three times the infrastructure cost per household as more compact areas. From a carbon emissions standpoint, this can add up quickly, with garbage trucks burning more gas to drive to these neighborhoods, roads requiring more asphalt and concrete, sewage requiring more pumps, etc.

Why isn’t America addressing this

I’m writing about this because housing density and transportation seem to be major blind spots in the American climate discourse. It wasn’t included at all in the IRA, and many environmental organizations and liberal politicians are actually fighting against dense housing. Here are some particularly egregious examples":

While many Democratic politicians across the country (including President Biden, Sens. Warren and Schatz, and Governors Polis and Hochul) have embraced building dense housing near transit, many local politicians in liberal cities like San Diego, San Francisco and New York who claim to care about the climate are pushing NIMBY policies that worsen sprawl and carbon emissions (and are responsible for our housing shortage)

Environmental organizations such as some chapters of the Sierra Club. A particularly egregious example was how a Bay Area Sierra Club Chapter and the Audobon Society sent a joint letter to the city of Mountain View, California, opposing new housing near transit because it would reduce the number of trees that drivers would see while driving on the highway. I wish I was making this up. The especially frustrating part here is that the Sierra Club’s national organization supports more housing near transit! But they delegate many local positions to local chapters that are run by NIMBYs who have completely lost the plot on this issue. I am optimistic, though, because younger climate activists are joining these organizations and taking leadership roles to get the Sierra Club back on track in places like San Francisco where pro-housing environmentalists recently turned the tide.

Additionally, some politicians make the argument that with the shift to EVs, public transportation and dense housing are no longer necessary. I wrote here about why this is incorrect, but the TL;DR is simply that EVs require far more resources (highways, metal/batteries, electricity, garage storage space) per capita than public transit.

Instead, politicians, organizations, and advocates who care about climate need to forcefully make the argument for building more, dense housing, particularly near transit. Some specific policies include:

Transit Oriented Development bills such as the federal Build More Housing Near Transit Act, New York Housing Compact, and Massachusetts Transit Oriented Communities law.

Broad upzoning bills like the one passed in Minneapolis, which resulted in a ton of new housing being built in urban, walkable, transit-oriented areas

Reforming of parking minimum laws that mandate new housing to be built with excess parking, which encourages car ownership and reduces transit ridership.

Streamlining housing construction so that new housing isn’t subject to frivolous lawsuits or arbitrary local reviews. In California, SB35 did this and resulted in over 18,000 new homes being built. (This bill is up for renewal, if you live in California please contact your state assemblymember and senator and tell them to support SB423)

Perhaps the most frustrating thing here is that most of these housing policies are popular and revenue-positive. It literally costs the government nothing to legalize dense housing, and the resulting increased land values will result in more property tax revenue! We just need climate-focused politicians and organizations to take a stance against NIMBYism and make it clear that it’s impossible to address climate change without building dense housing and making it easier for more people to take transit.

Transit expert Jarrett Walker has written “land use and transportation are the same thing described in different languages.” I have written that “ the single biggest factor in the carbon footprint of our cities isn't the amount of insulation in our walls, it's the zoning.” We have to face this.

Nice piece. Re. direct energy expenditure, the RECS data is helpful but doesn't correct for size, location, etc. I co-authored a piece in the Journal of Sustainable Economics that does those corrections -- and the result is even stronger. Just FYI: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10835547.2016.12091885